- The effects of the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine and the energy crisis are burdening private households and companies.

- Relief measures for private households and businesses need to be targeted and to preserve the incentive to save energy.

- Debt sustainability is not at risk in the medium term, but public finances should not be overstretched.

- Temporarily rely more on higher-income households to finance the relief measures, postpone remedies for bracket creep.

The sharp rise in energy prices puts a burden on private households and companies. Targeted relief is necessary to cushion social hardship and prevent jeopardizing the long-term economic development in Germany without placing an

excessive load on public budgets. Therefore, the relief measures should target those private households that cannot cope with the high energy prices, and to companies with a

medium-term business model that remains viable in the light of higher energy prices.

However, incentives to save energy must be maintained.

Public budgets have to shoulder the additional burden of financing future-oriented measures promoting energy security and defense capability, while the fiscal consequences of the coronavirus pandemic are still lingering. All of these measures have increased the public debt-to-GDP ratio. Nevertheless, public finances remain systainable in the medium term, also since the debt-to-GDP ratio was comparatively low before the crises. Moreover, it is likely to decline in the coming years due to the high nominal economic growth caused by inflation.

In 2020 to 2022, the German debt-brake exception clause was used to credit-finance economic stabilisation and the relief measures. "The economic consequences of the Russian war of aggression and the energy crisis could warrant suspending the debt brake in 2023 as well," says council member Achim Truger. Instead, the German government chose to shift financing to the Economic Stabilisation Fund, which does not contribute to the transparency of the budget and should be viewed critically.

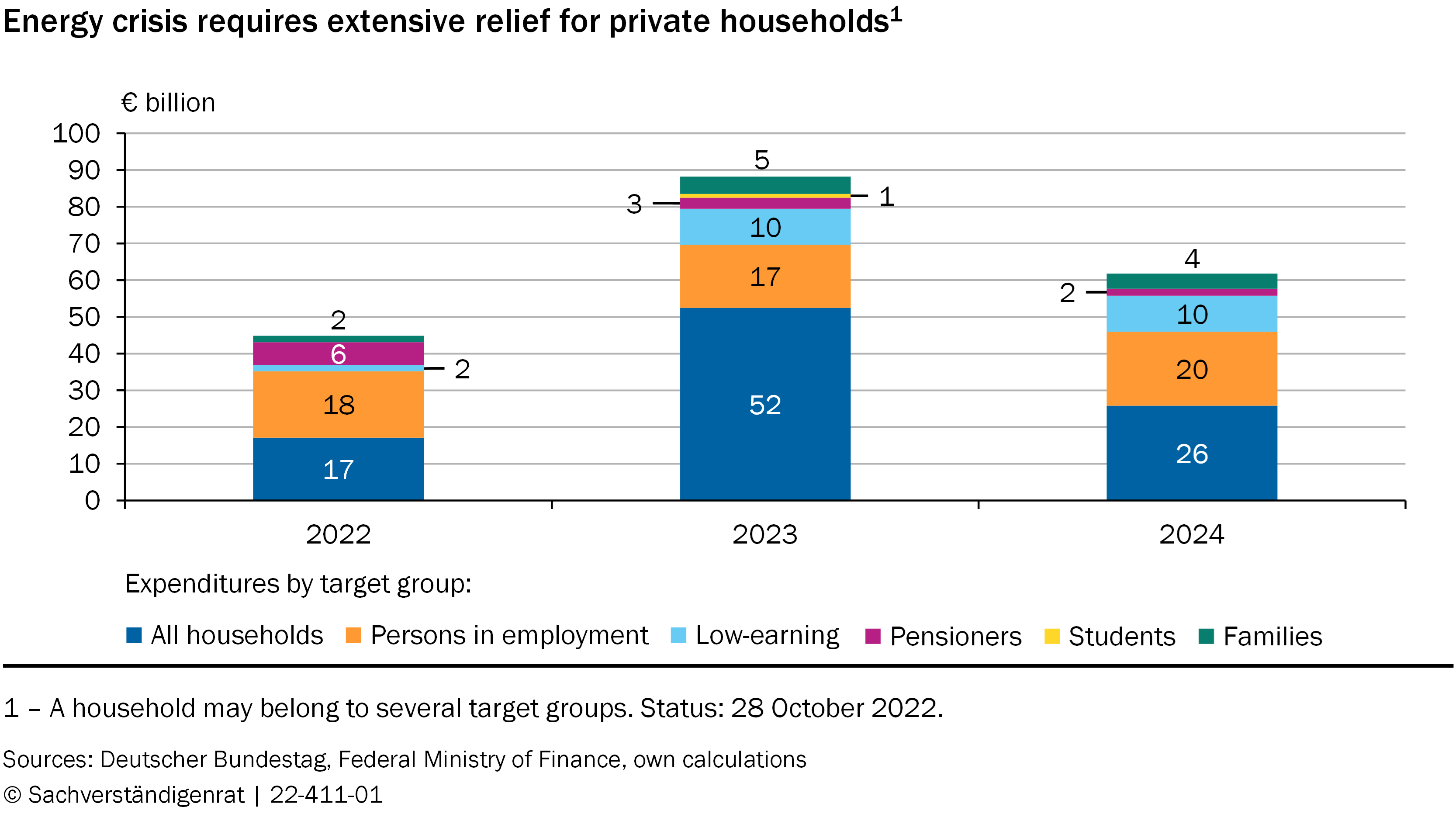

The rise in energy prices triggered extensive relief measures for households and businesses. Some of them are target households with low and medium incomes. A number of broad-based measures, however, such as the fuel discount, the reduction in value-added tax on natural gas, or the flat-rate benefits meant to reduce energy costs for all persons in employment, also accrue to high-income households that would be able to cope with high prices, and in some cases create false incentives. As a result, the fiscal burden and inflationary demand stimuli are higher than necessary.

Against this background, the timing for reducing the bracket creep in the income tax system seems inappropriate. Although its reduction is correct from a tax-system point of view, it should be postponed. If the top tax rate were increased for a limited period of time or an energy solidarity surcharge were introduced for high-income earners, part of the relief measures could be financed without additional debt. This would limit government borrowing and, at the same time, reduce the inflationary effect of the relief. This would make the overall package of reliefs and burdens more targeted.

So far, there is no instrument that allows for a targeted, income-based relief of households in the form of means-tested one-off payments in an unbureaucratic and timely manner. Such an instrument should be created urgently.